Determing the role of genotype and enviroment in shaping individual nuclear contributions to gene expression

Transcription is an essential step in linking genotype to phenotype, both during growth and in response to environmental changes. In dikaryotic basidiomycete fungi, transcription occurs seperately in each haploid nucleus, but translation happens in the shared cytoplasm. How (if at all)

transcription is coordinated between each nucleus is unknown, and previous evidence from

Agaricus bisporus suggests that one nucleus might sometimes be transcriptionally dominant over the other.

Additionally, the phenotype of dikaryotic fungi is not always correlated with the phenotypes of each monokaryon on its own.

I am researching how interactions between nuclear and mitochondrial genotypes, and enviromental stress, impacts how much each nucleus contributes to gene expression, ultimately helping us

better understand how fungi adapt and/or react to their enviroment.

Rethinking terminology for fungal sex

Mycologists have imported animal sexual categories, like male and female (and even the concept of sex

categories themselves), into fungi. However, the use of this terminology when talking about

fungal sex is not appropriate or accurate. In fact, fungal sexual reproduction is incredibly diverse, and

studying it can help all biologists better understand the evolution of sex. I am working on

critiquing and rethinking how we talk about fungal sex in order to better represent fungal biology, and avoid

using harmful and loaded language.

- Young, S.E., and Pringle, A. (2026). The limits of a love affair with analogy:

23,000 sexes and the fungus Schizophyllum commune. Philosophy,

Theory, and Practice in Biology 18(1). DOI:10.3998/ptpbio.6744.

- Young, S.E., McDonough-Goldstein, C., and Pringle, A. (in review). The (mis)use of sex categories in fungi.

Past Research

Characterizing the genomic organization of ant-associated Leucoagaricus spp.

In contrast to many basidiomycetes, some ant-associated

Leucoagaricus spp. are polykaryotic, with between 4-30 nuclei per cell instead of the usual two.

Using flow cytometry and whole genome sequencing, my work aimscharacterizing both how many distinct genome types (equivalent to ploidy) are present

in individaul strains, and how genome types are distributed between different nuclei.

- Manuscript in preperation

Image of a multinucleate Leucoagaricus cell. Nuclei are stained in blue and septa is indicated with arrow

Image of a multinucleate Leucoagaricus cell. Nuclei are stained in blue and septa is indicated with arrow

Characterizing the mating-type loci in Escovopsis

Escovopsis is a fungal parasite of

Leucoagaricus and likely followed

Leucoagaricus

into the fungus-growing ant symbiosis. Previous genomic analyses have suggested that

Escovopsis has

lost it's mating-type loci, which are the master regulators of sexual reproduction in fungi. I am working on

understanding the evolution, and potential loss, of the mating-type loci in

Escovopsis.

- Young, S.E., Bryan, C.T., Gotting, K., and Currie, C. (in revision). Evidence for cryptic sex in Escovopsis,

a mycoparasite in the fungus-growing ant symbiosis. Genome Biology and Evolution.

Escovopsis overgrowing a fungus garden composed of Leucoagaricus tissue

Escovopsis overgrowing a fungus garden composed of Leucoagaricus tissue

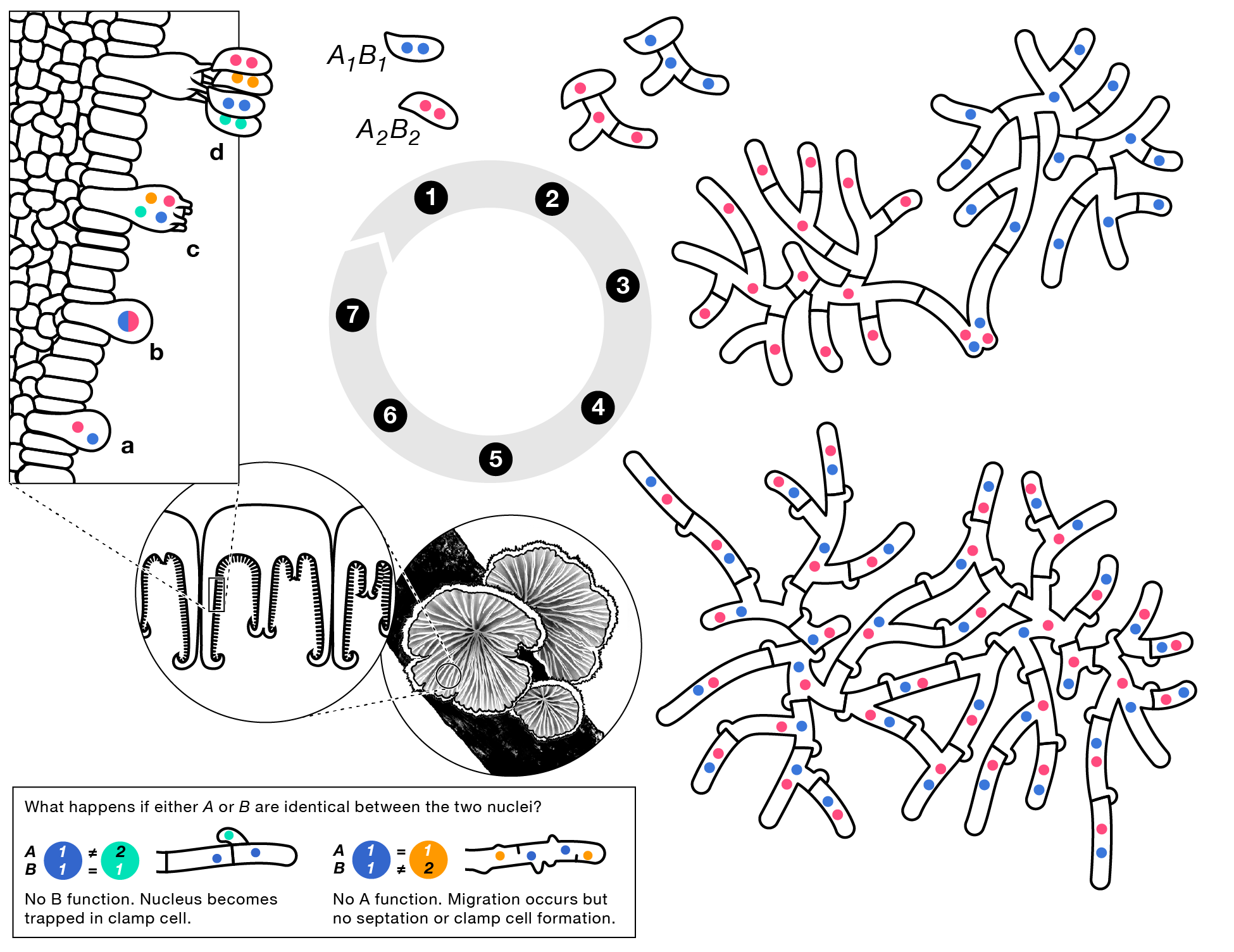

The lifecycle of Schizophyllum commune, showing a prolonged dikaryotic stage (4).

The nuclei only fuse in the basidospore producing cells in the mushroom (7). A and B refer to

mating types, which control the ability of monokaryons (2) to form dikaryons with each other.

Illustration by Sarah Friedrich, from Young and Pringle (2026).

The lifecycle of Schizophyllum commune, showing a prolonged dikaryotic stage (4).

The nuclei only fuse in the basidospore producing cells in the mushroom (7). A and B refer to

mating types, which control the ability of monokaryons (2) to form dikaryons with each other.

Illustration by Sarah Friedrich, from Young and Pringle (2026).

Image of a multinucleate Leucoagaricus cell. Nuclei are stained in blue and septa is indicated with arrow

Image of a multinucleate Leucoagaricus cell. Nuclei are stained in blue and septa is indicated with arrow

Escovopsis overgrowing a fungus garden composed of Leucoagaricus tissue

Escovopsis overgrowing a fungus garden composed of Leucoagaricus tissue